Home | About Bequia | Travel | Where to Stay | Activities | Shops & Services | Summer Specials | Links | Contact

|

|

|

|

Bequia's earliest

inhabitants, dating back to the first centuries of the

first millennium AD, were pottery-making Amerindians

whose origins lay in the northern coastal regions of

South America. Travelling in large dug-out canoes, they

came in successive waves of migration up through the

islands, with the smaller islands such as Bequia being

the last to be occupied on any meaningful or permanent

basis.

Around 14/1500 AD there was a final wave of migration into the region, this time bringing what are now known as the Island Caribs or Kalinago, who assimilated themselves into the existing indigenous population and absorbed most of their culture. It was these same Caribs in the Lesser Antilles who later tried to resist the onslaught of European colonization in the Antilles in the 16th and 17th centuries; driven out from other islands in the Antillean chain, they finally made the island of St. Vincent their homeland. By the mid to late 1600s, the population of indigenous ("Yellow") Caribs in St. Vincent had been considerably augmented by runaway or shipwrecked Africans especially on the Windward side of St. Vincent, giving rise to what became known as the Black Caribs or Garifuna. So determined was the resistance of these Caribs to European settlement that both the French and the English essentially agreed to leave the Caribs of St. Vincent in peace, despite both countries' desire for further colonisation of economically promising 'new' lands. (Less promising were the Grenadines: A 1659 account of the French Antilles describes Bequia itself as being "too inaccessible to colonise", and used only by Caribs from St. Vincent for fishing and for "cultivating little gardens".)

It was a different story though for Bequia and the other small Grenadine islands which at this time were administratively part of French-owned Grenada and very much under French control from Martinique. Whilst considered ideal for careening, (Blackbeard's notorious Queen Anne's Revenge was fitted out in Bequia using a French merchant ship captured off St. Vincent in November 1717), illicit trading, turtle fishing and as a source of lumber, Bequia remained an otherwise unsettled and undeveloped outpost. Nevertheless, certainly from the early 1740s onwards, British ships were actively banned from setting ashore for wood, water or other supplies and French ships rigorously patrolled throughout the Grenadine waters. As Grenada's economy become more sugar-based, sugar began to overshadow the less labour-intensive production of indigo, cocoa and cotton, first Carriacou then the more distant Bequia slowly became potential alternatives to people with more modest aspirations. Small numbers of French adventurers from both Grenada and Martinique, who had not found success in the bigger islands and had only limited financial and labour resources, found themselves drawn to the possibilities presented but these small, less-frequented islands - excellent protected bays, some reasonably good flat land and above all, far from the watchful eye of the centres of government. By about 1750, a handful of French families and their enslaved workers, probably numbering no more than about 40 people in total, had started to settle in Bequia. In the following decade land was granted and cleared, indigo, cocoa and latterly cotton were planted, turtles (much valued for their shells) were fished and lime was processed. The island’s tiny population was then made up of a few “French whites”, some "free coloureds", a relatively small number of enslaved workers and perhaps a few resident Black Caribs. Traces of French works and roads can still be found on parts of the island, and, as in St. Vincent, many locations - and indeed families - still carry French names.

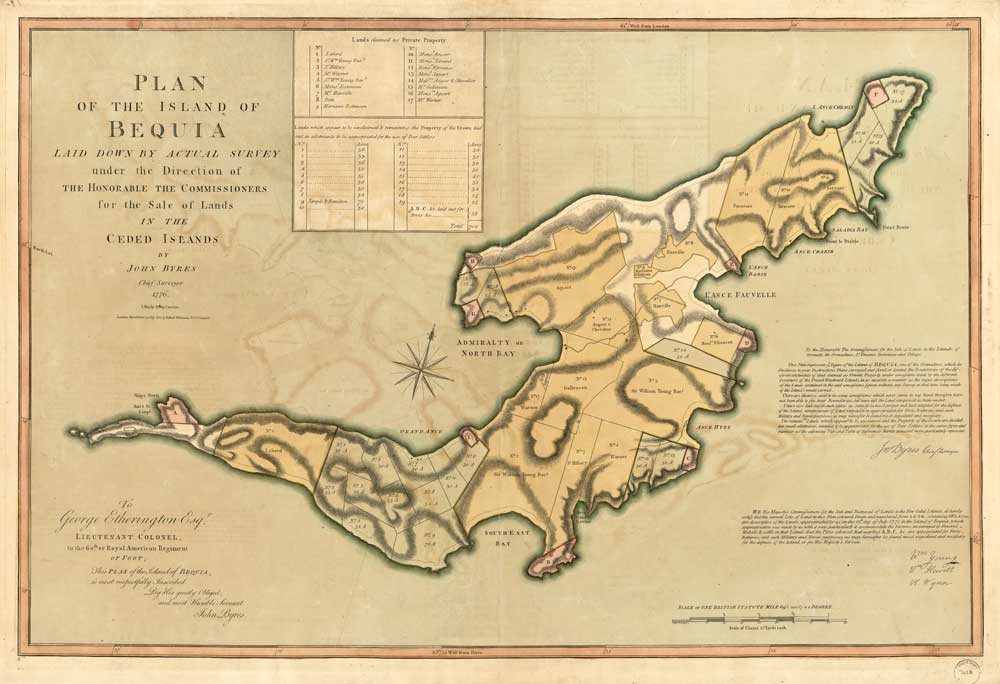

In the years immediately following the Treaty of Paris, whilst the existing French settlers on Bequia were at least allowed to retain the acres they had cultivated and cleared (if they could prove title), the lion's share of the island's prime land was typically acquired either by the British elite involved in surveying the island, or by existing landowners or merchants based elsewhere in the British West Indian islands. These first “investors” in Bequia, French and British, either quickly expanded and developed their land into working sugar plantations, or sold on their allocations to others who were eager to capitalise on the wealth they believed owning a sugar plantation in the “Ceded Lands” would bring. Much smaller tracts of land - nineteen in total and by definition considered unsuitable for the cultivation of sugar - were offered as approximately 30-acre grants to less fortunate British subjects, (so-called "poor settlers") with a view to urgently encouraging the establishment of a viable community which would support and function alongside the sugar production that was getting underway on the island.  Bequia c. 1771, surveyed by

John Byres for the “Commissioners for the Sale

and Disposal of the

New Ceded Lands in the Islands”, showing the 19 lots of land set aside for "poor settlers" (published 1776) This small group of tradesmen,

mariners, craftsmen and hardy smallholders

numbering probably no more than 90 in total

including wives, children and their few slaves

were, at least in

part, likely descended from those 17th

century settlers and indentured servants who had

earlier been displaced from small farms or

exhausted plantations elsewhere in the British

West Indies. The grants of land on offer in

Bequia presented an opportunity to acquire a

small acreage of virgin land in this newest

British territory, and offered hope that with

hard work, a good living might be finally made

which would lead to a brighter future.

Several of

these 15 or so families and individuals came

from the tiny, volcanic island of Saba, close

to St. Kitts and Statia, and at 5 square

miles, not dissimilar in size to Bequia’s

seven. Unlike the island’s plantation owners

who mostly left following Emancipation in 1838

if not before, it is these earliest settlers,

their descendants and those of the former

enslaved labourers, who became the backbone of

Bequia’s post-Emancipation community and who

remain so to this day.

St. Kitt's itself was another island from which settlers came to Bequia. The first British owners of Bequia's Spring, Mount Pleasant and Belmont estates came from this then part-British, part-French sugar-producing island, as did James Hamilton, father one of the Founding Fathers of the United States of America, Alexander Hamilton. Formerly a clerk in St. Kitt's, James Hamilton applied for land as a "poor settler" probably in the late 1760s, and was granted 25 acres on the north shore of Admiralty Bay, adjoining the land set aside for the heavily fortified battery that was soon to be constructed. It is after "Hamilton;s Land" that the fishing village of Hamilton was named.

Bequia’s plantations may have become exhausted and unproductive, but the waters surrounding the island were always wonderfully rich fishing grounds. In the early 19th century, Yankee whalers frequently ventured south to the Grenadines in search of their catch, so whaling and the processing of whale products was a familiar activity in the country, most particularly to those living on the south side of Bequia. One young Bequian, William “Old Bill” Wallace Jr., son of the late, Scottish-born owner of the large, but by now defunct sugar plantation in Friendship, determined that whaling would be the key to the future of his island and its struggling population. He left home in 1855 at the age of 15 to work as an apprentice on a New England whaleship. He returned to his native island in the late 1860s with two New England whaleboats, the Iron Duke and the Nancy Dawson, ready to commence his whaling operation in Friendship Bay. A second station - set up by landowner Joseph "Pa" Ollivierre, son of a Bequia-based French cotton planter - swiftly followed, and whaling went on to become the premier economic activity on the island for many years to follow. Whale oil and whale bone were not only valuable exports they were also an important source of lubrication, medication, fuel for lighting, and raw material for furniture and construction. Whale meat itself became - and still remains - a staple protein-rich food and source of income for many Bequia families. It was not long before Bequia became renowned for her uniquely successful whaling fleet and her heroic whalermen.

But it was the building of whaleboats in the closing decades of the 19th century, and the boon that that activity provided to the island as a whole, that gave the real impetus for the rapid development of Bequia's home-grown boat-building into a thriving industry. In just ten years, between 1871 and 1881, the number of mariners and shipwrights on the island increased from 73 to 157. Boats of all sizes, from 27ft whaleboats to large island schooners, were soon to be built on beaches all over the island - at Friendship Bay, Lower Bay, La Pompe, Paget Farm, Hamilton, Belmont and in the heart of Admiralty Bay, then known as Bequia Town. A resettlement scheme for “poor whites” from Barbados brought a fresh influx of families and skills to the island in the 1860s. Settling almost exclusively in Mount Pleasant, these new arrivals would later contribute significantly to the existing fishing and boatbuilding activities on the island. In the 20th century, boat and ship-building in Bequia continued to dominate over the rest of the Grenadines. Of the 153 ships registered as having been built in St. Vincent & the Grenadines between 1923 and 1990, no less than 71 were built in Bequia by thirty-seven of the island's boatbuilders, which included Barbados-born Walter Sargeant and Dillon Pollard who came to Bequia as shipwrights' apprentices in the late 19th/early 20th century.

Launching of the 165ft Gloria Colita

February 1939

Reginald Mitchell came from a richly talented Bequia boat-building family. His father James Fitz Allen ("Uncle Harry") Mitchell was one of three boat-building sons of William Mitchell and Mary Compton, daughter of English-born shipwright Benjamin George Compton who had emigrated to the Grenadine island of Canouan probably some time in the 1830s. Reginald’s mother, Sarah Ann Ollivierre, was the granddaughter of Joseph” Pa” Ollivierre, co-founder of Bequia’s whaling industry.

Universal adult suffrage was granted to the people of St. Vincent & the Grenadines in 1951. Like its Windward Island neighbours, St. Vincent was by this time resolute in seeking freedom from nearly 250 years of British rule. Associate Statehood status, giving control over its internal affairs, was granted in October 1969 and ten years later, in October 1979, the multi-island state of St. Vincent & the Grenadines finally became an independent nation. For its part, Bequia still retains its unique and proud seafaring heritage, its own fierce sense of independence and its age-old, open-hearted welcome for visitors from other shores. Today's Bequians are for the most part direct descendants of those African, Carib, French, English, Irish, and Scottish settlers, smallholders, labourers and enslaved individuals who came to the island in the 18th and 19th centuries and who chose never to leave - or at least always to return. And Bequia is still casting that spell. Many of its more recent "settlers" from America, Canada and Europe came once, came again, then finally made their homes here. Visitors too return year after year, eagerly anticipating that special warmth that is shared by Bequia and its people.

Nicola Redway - Trustee, Bequia Heritage

Foundation

The Bequia Heritage Museum  The Bequia Heritage Museum - opened

officially on December 15th 2020 - represents the

fulfilment of nearly thirty years of planning,

fundraising and aspiration by the Trustees of the

Bequia Heritage Foundation, spearheaded by the late

Pat Mitchell.

Designed by Bequia architect Thomas Dehen, the Museum complex at St. Hillary now comprises two buildings with interrelated exhibits. The spacious, airy Boat Museum (opened in November 2013) explores Bequia’s famed maritime history, including boat-and shipbuilding and whaling. It also includes a traditional Amerindian dug-out canoe, there to represent the mode of transport and migration of indigenous people who settled and lived both in Bequia and, more broadly, in the region as a whole going back thousands of years. Outside there are other relics of bygone eras on display. Visitors can also enjoy a spectacular view of Friendship Bay and nearby islands from the building’s shady wrap-around terrace.  Boat Museum at Bequia Heritage Museum Next door, the newly completed

air-conditioned Annexe, with its fine

display of Amerindian pottery and artefacts

almost all found on Bequia, together with a

selection of items dating from the European

period of Bequia’s settlement, including a

collection of bottles retrieved from Admiralty

Bay, expands on and completes the unique arc

of Bequia’s 1700 year history.

New Annexe Gallery at Bequia Heritage Museum Illustrated PowerPoint Presentations in the Annexe Gallery augment the displays in both buildings with detailed background history, plus maps, charts, documentation, commentary and early photographs. Reproductions of rare antique Bequia maps, postcards and books are also available to purchase. On display outside the Annexe is the whale boat Rescue, de-commissioned by its owner Orson Ollivierre when he decided to lay down his harpoon and turn instead to whale watching. Our dedicated and knowledgeable Museum Representatives are on hand to welcome you and guide you through the exhibits. Allow plenty of time for your visit and to take in all the detailed information on offer from our guides, and to enjoy the beautiful and tranquil location. In depth, out-of hours private tours with one of our Trustees are available by prior arrangement. Pre-booked school trips are also both welcome and actively encouraged. Read recent

visitors comments HERE

Museum Opening Hours: Currently Monday, Wednesday & Friday 10AM – 1PM (closed in September and early October) Private Guided Tours and School Visits by prior arrangement. Admission in regular hours: EC$25 per person (kids under 12 free with adults) Groups of 6 or more - 20% discount after the first 6 Open Days: Check local press and social media for Saturday open days! For more information or to book a guide tour: Email: bequiaheritage@gmail.com Tel: 1 (784) 532-9554 (museum hours) OR Tel: 1 (784) 532 9554 / 457 3649 (out of hours) Have you visited the museum and want to give your feedback? Email: bequiaheritage@gmail.com The creation of the Bequia Heritage Museum complex has been made possible primarily through significant funding by the Grenadines Partnership Fund, as well as generous donations by private individuals and Bequia lovers. Following the completion of the Annexe, the Trustees will now turn their attention to developing the rest of the site at St Hillary, which reaches right down to the sea.  Proposed Scheme for future development of Bequia Heritage Museum Site at St. Hillary Click here to enlarge Future plans for the site include The Pat Mitchell Cultural Centre for performing arts, installations for living heritage activities such as cassava processing, basket weaving, and boat building, the installation of a typical Bequia house preserved and relocated for posterity, and the creation of the Morris Nicholson Memorial Garden. This garden – and the completion of the Annexe – is thanks to the generous support of the Koven Foundation and the Klipstein Foundation in memory of their friend, Bequia resident and world-class skipper, Morris Nicholson. |